Content Strategy combines what project stakeholders want to publish with what the public wants to know, and figures out the best way to present it. Read how.

A.E.Veltstra

Nov. 13, 2014

Websites generally contain a few articles most readers have learnt to expect:

If your web site lacks these pages, people will be at a loss, and may look for other ways to get to this information, or will simply go aeay and spend their money elsewhere. This is because after roughly 20 years of WWW history, a lot of the successful web sites do contain those pieces of information, and make them readily available and easily found.

(Don't take our word for it. Look up Vincent Flanders, Jakob Nielsen, and Peep Laja: they say the same.)

So, apart from those standard web pages, what else should someone publish on their web site? To answer that question, a new field of study has emerged from a combination of corporate communication and information architecture: Content Strategy.

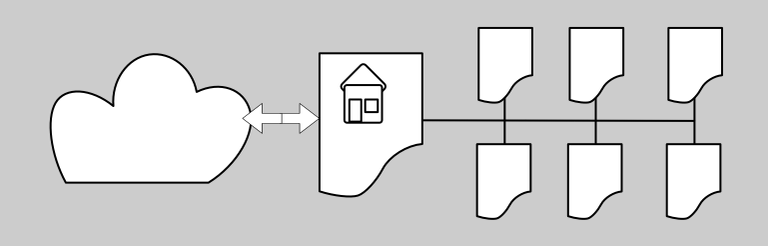

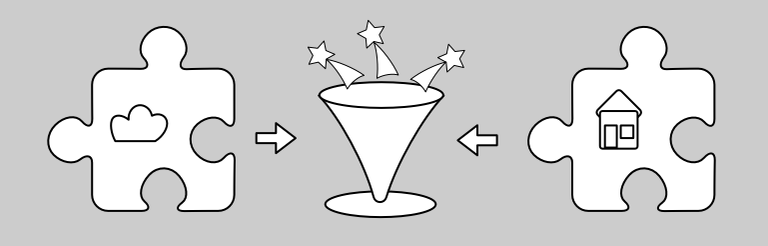

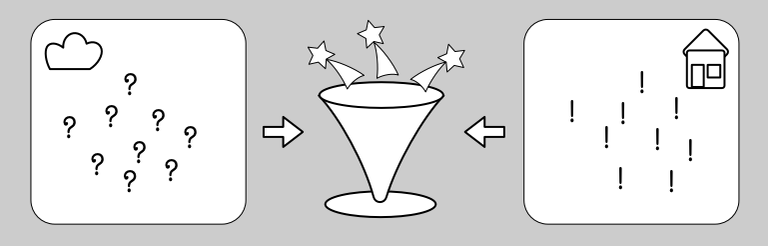

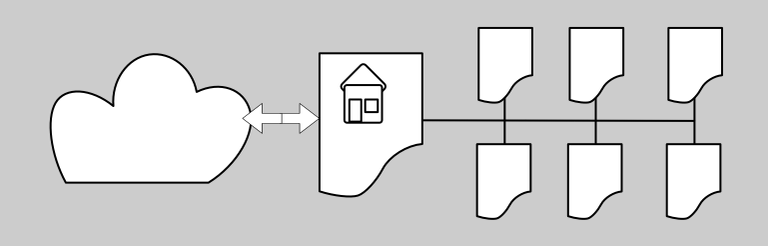

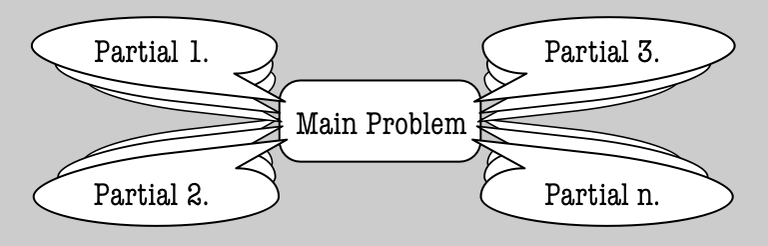

Content Strategy looks at what it is that project stakeholders want to publish, combines that with what the public wants to know, and figures out the best way to present it at that moment in time.

This last bit is important: over time, what an audience or potential customer wishes to see, and thus what a web site should show, will change. Even the list of standard information presented above is likely to change. It is not a matter of whether, but of when. And your web site should be outfitted with ways of measuring that change. Therefore, analytics play a big role in content strategy.

It will sound like we are kicking in an open door, but yes: we start with the project stakeholders, like any other Information Architecture. We want to know who they are, what they expect from the web site, what problem it is that the web site needs to solve.

Sometimes our clients start at the wrong moment. They come to us with the request to build a web site for them. "Why?", we ask. "Because the competition has one, too." OK, valid reasoning, but the wrong moment to choose a web site. For now the question becomes: what do we do with it once we have it?

That is the wrong question.

The question should be: what is your problem? Then a web site may be posed as part of the solution. For that way, we can put in evaluation moments (KPI, or Key Performance Indicators), to determine whether the current product (the web site) functions to solve the problem, or whether additional work is needed.

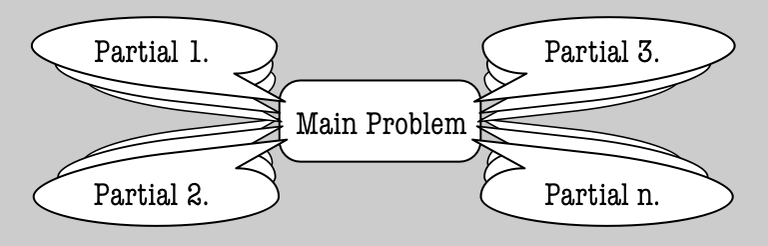

So talk to the project stakeholders. Draw a diagram of their main needs and wants, get back to them within a week to check whether you have it right, and then touch base with them about 2 weeks later to ensure their ideas haven't changed.

If the stakeholders' ideas did change within those 3 weeks, propose an agile project process. If they stayed the same, propose a waterfall process.

It highly depends on what the stakeholders do.

A school or university will want to show off their curriculae, their departments, success rates, and who their professors and directors are. Many stakeholders will want to see their own name and picture on the front page, or at least their pet project.

An audience of potential students looking up school information may seek different information: where are the departments located, do they have dorms, how much do the trajectories cost, how to apply for grants, and how to enroll.

Both groups may want the web site to provide enrollment.

Existing students and professors may want a way to share their homework and test scores, or even take courses online.

Now, where do we put the pages in the site, and what title and description do we assign them?

For this, we can use a technique that lets us group and stack information cards. Bring in people from each group of stakeholders, let them write the title of a page on an index card, and then let the group sort and stack these index cards. Chances are together they will find an order that makes most sense to most people.

You can repeat that with a different group of people. Ask people from your immediate circle of friends, too. This lets you recognise how each group's needs and expectations differ.

Remember that any such sorting is transient: over time, what appears the best order is likely to change.

Now there is also a line of thinking (by advocates of semantic optimisation) that advocates using public-actionable page titles. Rather than telling the public what the web site owners think, we let the web site solve problems the public has.

That means this is a bad title: "our history", and this is a good one: "learn about our history". This is worse: "products", and this is better: "browse our products". This is worse: "Dr. Johnson", and this is better: "Meet your future Professor of Communication." Do not allow space constraints to reduce clarity!

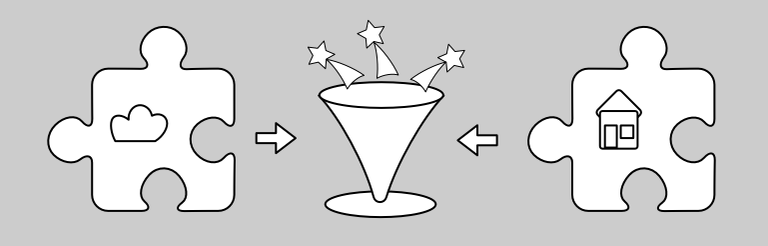

(This, by the way, is why one should know the Content Strategy before deciding on the visual display of the product: the visuals should fit the content, and not the other way around.)

Part of this is choosing each web page's web address. Proponents of the semantic web (which includes search engines like Google and Bing) advise us to use a handful of words that describe the page best. Use brand names only after making it clear what a brand-named product does, unless your client's products are so well-known that readers are looking for them, specifically. (That would make them Coca Cola or Mars. Are they?)

The ever insightful Jakob Nielsen proposes an inverted pyramid writing style combined with easily scanned paragraphing. Basically you start with the conclusion, and you add more and more detail as you go on.

The idea that people don't read long articles is plain wrong, and demonstrably wrong. (You are my evidence, but please also look at analysis performed by Peep Laja from ConversionXL.) What we seem to need is easily-scanned paragraphs: bigger headings and cursived emphasis.

(You may also see these same hints when you learn about content marketing, but they go one step further: instead of a title that tells the audience what they expect to find, content-marketers use titles that invoke a strong emotion in the reader. This technique certainly has proven its worth... but it usually turns out to be click bait for advertisement sales, rather than professional corporate material. Hint: avoid.)

The idea that people don't read articles without graphics is wrong too, but Peep Laja has shown that articles with graphics do get more views... even if the graphic is entirely unrelated.

You may think this belongs in the visual design department. And in part that is true. However, there is an important amount of standards; historically grown expectations, which show up time and time again in eye-tracker heat maps. These heat maps really help determine whether a page layout draws attention to those elements which the owner considers most important.

These maps tell us that people in our cultures (western Europe, America, Australia, and other similar ones) read web pages from left to right and from top to bottom, much like the books and newspapers we read. They also tell us that people scan articles for interesting topics.

This determines that the top left part of the page should provide the most important information of the web page. What is that? It's what a visitor needs to determine whether they are at the right place, looking at the right content.

The best for this is a combination of the page's title and the web site's logo.

Near this we find a good place for a title image. Any nice picture will do. If you can find a picture that fits the topic, use it. Remember to pay for royalties!

To the right a reader will expect a search box and some hyperlinks to utility web pages (contact, site map, etc.)

Underneath that, visitors expect a short introduction. If we use an inverted pyramid (as suggested above) for our content, the title should be the article's conclusion, and the intro may use 140 to 200 letters to expand upon that. (Whether the content authors get this right or not can be seen using page analytics.)

Then the rest of the article should follow. Use short paragraphs. Don't intersperse the text with adverts: this confuses the readers and pulls them away from the article. Do intersperse the text with illustrations (but avoid happily smiling actors from stock photos).

If the web site is authored by multiple authors, do add an author photo and a short author biography.

To increase communication between visitors and owners, the content author should ask the reader a non-rhetorical question, and the page should provide a commenting function.

To lead the reader to another page, provide a list of links to related articles.

Please don't split up the page if the article is long. People using mobile devices with limited bandwidth will thank you. Besides, splitting pages is done only to sell more ads, and your client is not one of those, are they?

Remember that these hints are valid for a limited amount of time: they became valid about 2 years ago, and they are likely to change within a couple years. The solution to that is to keep testing.

Then we test whether a different content offering, page structuring, page titling, or visual display works better. For these test we can use an A/B-tester, or a multi-variate tester.

It's best if these tests are built into the web site's publishing system. Otherwise, one could employ tools like Google's Web Site Optimiser.

Both a technical and a non-technical discussion.

Someone will need to be writing up all that information the web site owner wants to share. Sometimes a lot of information already exists in some form and needs to be transformed. For a corporate or university web site, it takes quite a bit of preparation before publishing the first pages. A good project manager can let the web site go live with most primary content available.

For smaller organisations or singular individuals, the work will fall to them, entirely, unless they can hire content editors (Fiverr?) or invite guest bloggers.

In either case, the authors need a way of publishing their articles, and they need to be organised.

An exception to this is when the web site is a social media sharing platform (Facebook, Google Plus, Twitter) or a community discussion platform (vBulletin, phpBB), where it is not the site owners writing up articles, but the site members whose sharings populate the site. Then maybe some documentation is needed to inform the members how the system works and what the rules are for using it, and the rest of the content is added later by the members.

Then the question becomes: how often will new articles be added, and how often will existing ones be checked or revoked? Will new publications be distributed to RSS and social media automatically? Or will a web-care team need to be informed about publications?

How often one publishes new content greatly depends on the web site owner and the web site members. In larger organisations, a publication workflow may be suggested (who does what, when, and who checks it when, and who will fix any errors?) In smaller organisations, publications may start out regularly, and then slow down when the web site owner runs out of new material. (Really, how many articles can one write about the art of Zen and repairing motorbikes?)

Who does the work, and how often publication takes place, and whether it's shared to RSS and social media, must all be considered in choosing a software system and setting up work policies.

A good consultant should educate their clients about their choices and then help choose a system and help set up policies based on their clients' requirements.

A bad consultant will pick a software system and force their client to fit into it.

And with that we have reached the end of this article. What methods do you prefer to create a content strategy? Please leave a comment below!

- a home page (presenting the company or person);

- contact information;

- an 'about us';

- a privacy policy (how will they use my information?);

- policies regarding shipping and delivery for web stores;

- a news room (mostly geared to news agencies);

- a site map for visitors and one for search engines;

- a search results overview;

- a shopping cart for web stores;

- account management for any web site where a client signs in.

If your web site lacks these pages, people will be at a loss, and may look for other ways to get to this information, or will simply go aeay and spend their money elsewhere. This is because after roughly 20 years of WWW history, a lot of the successful web sites do contain those pieces of information, and make them readily available and easily found.

(Don't take our word for it. Look up Vincent Flanders, Jakob Nielsen, and Peep Laja: they say the same.)

So, apart from those standard web pages, what else should someone publish on their web site? To answer that question, a new field of study has emerged from a combination of corporate communication and information architecture: Content Strategy.

Content Strategy looks at what it is that project stakeholders want to publish, combines that with what the public wants to know, and figures out the best way to present it at that moment in time.

This last bit is important: over time, what an audience or potential customer wishes to see, and thus what a web site should show, will change. Even the list of standard information presented above is likely to change. It is not a matter of whether, but of when. And your web site should be outfitted with ways of measuring that change. Therefore, analytics play a big role in content strategy.

How to start

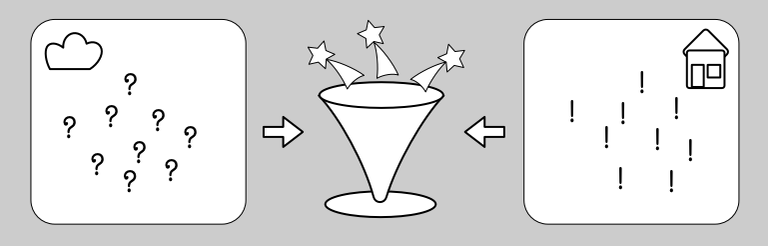

It will sound like we are kicking in an open door, but yes: we start with the project stakeholders, like any other Information Architecture. We want to know who they are, what they expect from the web site, what problem it is that the web site needs to solve.

Sometimes our clients start at the wrong moment. They come to us with the request to build a web site for them. "Why?", we ask. "Because the competition has one, too." OK, valid reasoning, but the wrong moment to choose a web site. For now the question becomes: what do we do with it once we have it?

That is the wrong question.

The question should be: what is your problem? Then a web site may be posed as part of the solution. For that way, we can put in evaluation moments (KPI, or Key Performance Indicators), to determine whether the current product (the web site) functions to solve the problem, or whether additional work is needed.

So talk to the project stakeholders. Draw a diagram of their main needs and wants, get back to them within a week to check whether you have it right, and then touch base with them about 2 weeks later to ensure their ideas haven't changed.

If the stakeholders' ideas did change within those 3 weeks, propose an agile project process. If they stayed the same, propose a waterfall process.

What information do the stakeholders want to publish?

It highly depends on what the stakeholders do.

A school or university will want to show off their curriculae, their departments, success rates, and who their professors and directors are. Many stakeholders will want to see their own name and picture on the front page, or at least their pet project.

An audience of potential students looking up school information may seek different information: where are the departments located, do they have dorms, how much do the trajectories cost, how to apply for grants, and how to enroll.

Both groups may want the web site to provide enrollment.

Existing students and professors may want a way to share their homework and test scores, or even take courses online.

Now, where do we put the pages in the site, and what title and description do we assign them?

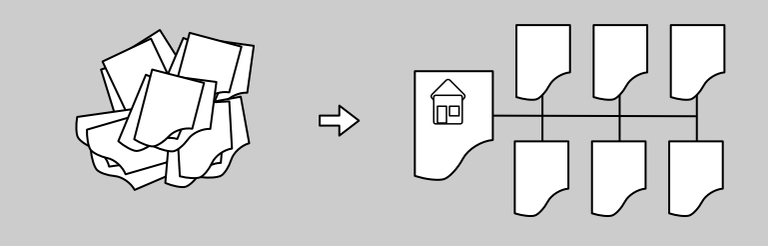

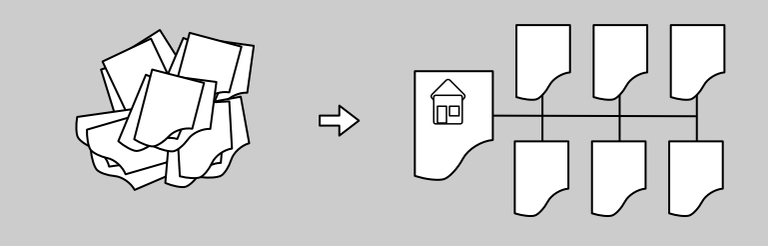

For this, we can use a technique that lets us group and stack information cards. Bring in people from each group of stakeholders, let them write the title of a page on an index card, and then let the group sort and stack these index cards. Chances are together they will find an order that makes most sense to most people.

You can repeat that with a different group of people. Ask people from your immediate circle of friends, too. This lets you recognise how each group's needs and expectations differ.

Remember that any such sorting is transient: over time, what appears the best order is likely to change.

Now there is also a line of thinking (by advocates of semantic optimisation) that advocates using public-actionable page titles. Rather than telling the public what the web site owners think, we let the web site solve problems the public has.

That means this is a bad title: "our history", and this is a good one: "learn about our history". This is worse: "products", and this is better: "browse our products". This is worse: "Dr. Johnson", and this is better: "Meet your future Professor of Communication." Do not allow space constraints to reduce clarity!

(This, by the way, is why one should know the Content Strategy before deciding on the visual display of the product: the visuals should fit the content, and not the other way around.)

Part of this is choosing each web page's web address. Proponents of the semantic web (which includes search engines like Google and Bing) advise us to use a handful of words that describe the page best. Use brand names only after making it clear what a brand-named product does, unless your client's products are so well-known that readers are looking for them, specifically. (That would make them Coca Cola or Mars. Are they?)

How about structuring actual content?

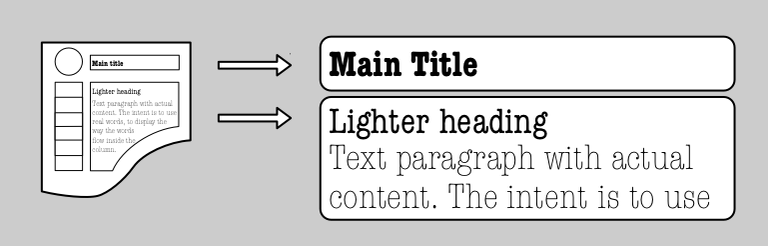

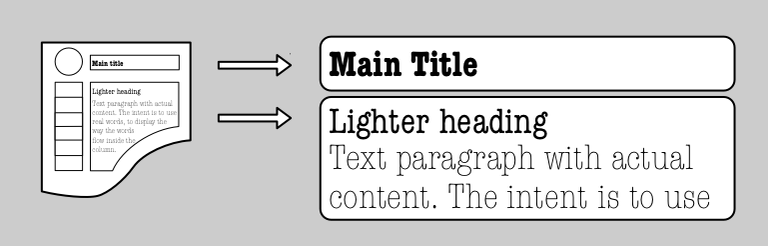

The ever insightful Jakob Nielsen proposes an inverted pyramid writing style combined with easily scanned paragraphing. Basically you start with the conclusion, and you add more and more detail as you go on.

The idea that people don't read long articles is plain wrong, and demonstrably wrong. (You are my evidence, but please also look at analysis performed by Peep Laja from ConversionXL.) What we seem to need is easily-scanned paragraphs: bigger headings and cursived emphasis.

(You may also see these same hints when you learn about content marketing, but they go one step further: instead of a title that tells the audience what they expect to find, content-marketers use titles that invoke a strong emotion in the reader. This technique certainly has proven its worth... but it usually turns out to be click bait for advertisement sales, rather than professional corporate material. Hint: avoid.)

The idea that people don't read articles without graphics is wrong too, but Peep Laja has shown that articles with graphics do get more views... even if the graphic is entirely unrelated.

Finally: Page Layout

You may think this belongs in the visual design department. And in part that is true. However, there is an important amount of standards; historically grown expectations, which show up time and time again in eye-tracker heat maps. These heat maps really help determine whether a page layout draws attention to those elements which the owner considers most important.

These maps tell us that people in our cultures (western Europe, America, Australia, and other similar ones) read web pages from left to right and from top to bottom, much like the books and newspapers we read. They also tell us that people scan articles for interesting topics.

This determines that the top left part of the page should provide the most important information of the web page. What is that? It's what a visitor needs to determine whether they are at the right place, looking at the right content.

The best for this is a combination of the page's title and the web site's logo.

Near this we find a good place for a title image. Any nice picture will do. If you can find a picture that fits the topic, use it. Remember to pay for royalties!

To the right a reader will expect a search box and some hyperlinks to utility web pages (contact, site map, etc.)

Underneath that, visitors expect a short introduction. If we use an inverted pyramid (as suggested above) for our content, the title should be the article's conclusion, and the intro may use 140 to 200 letters to expand upon that. (Whether the content authors get this right or not can be seen using page analytics.)

Then the rest of the article should follow. Use short paragraphs. Don't intersperse the text with adverts: this confuses the readers and pulls them away from the article. Do intersperse the text with illustrations (but avoid happily smiling actors from stock photos).

If the web site is authored by multiple authors, do add an author photo and a short author biography.

To increase communication between visitors and owners, the content author should ask the reader a non-rhetorical question, and the page should provide a commenting function.

To lead the reader to another page, provide a list of links to related articles.

Please don't split up the page if the article is long. People using mobile devices with limited bandwidth will thank you. Besides, splitting pages is done only to sell more ads, and your client is not one of those, are they?

Remember that these hints are valid for a limited amount of time: they became valid about 2 years ago, and they are likely to change within a couple years. The solution to that is to keep testing.

What if page views and customer conversions dwindle?

Then we test whether a different content offering, page structuring, page titling, or visual display works better. For these test we can use an A/B-tester, or a multi-variate tester.

It's best if these tests are built into the web site's publishing system. Otherwise, one could employ tools like Google's Web Site Optimiser.

Who will write the articles, when?

Both a technical and a non-technical discussion.

Someone will need to be writing up all that information the web site owner wants to share. Sometimes a lot of information already exists in some form and needs to be transformed. For a corporate or university web site, it takes quite a bit of preparation before publishing the first pages. A good project manager can let the web site go live with most primary content available.

For smaller organisations or singular individuals, the work will fall to them, entirely, unless they can hire content editors (Fiverr?) or invite guest bloggers.

In either case, the authors need a way of publishing their articles, and they need to be organised.

An exception to this is when the web site is a social media sharing platform (Facebook, Google Plus, Twitter) or a community discussion platform (vBulletin, phpBB), where it is not the site owners writing up articles, but the site members whose sharings populate the site. Then maybe some documentation is needed to inform the members how the system works and what the rules are for using it, and the rest of the content is added later by the members.

Then the question becomes: how often will new articles be added, and how often will existing ones be checked or revoked? Will new publications be distributed to RSS and social media automatically? Or will a web-care team need to be informed about publications?

How often one publishes new content greatly depends on the web site owner and the web site members. In larger organisations, a publication workflow may be suggested (who does what, when, and who checks it when, and who will fix any errors?) In smaller organisations, publications may start out regularly, and then slow down when the web site owner runs out of new material. (Really, how many articles can one write about the art of Zen and repairing motorbikes?)

Who does the work, and how often publication takes place, and whether it's shared to RSS and social media, must all be considered in choosing a software system and setting up work policies.

A good consultant should educate their clients about their choices and then help choose a system and help set up policies based on their clients' requirements.

A bad consultant will pick a software system and force their client to fit into it.

That's all, folks!

And with that we have reached the end of this article. What methods do you prefer to create a content strategy? Please leave a comment below!

Need problem solving?

Talk to me. Let's meet for coffee or over lunch. Mail me at “omegajunior at protonmail dot com”.